An ode to grace …

So, there I was, awkwardly adrift in the cultural hellhole that was the early ‘70’s on Tyneside and entranced by an exotic sport held mainly in distant countries and with no media support to fuel a burgeoning fascination. In a time long before even World of Sport began their token showing of less than 1% of the world’s greatest, most gruelling, sporting extravaganza, the Tour de France, options for following races were as limited as your chances of buying a white Model T Ford.

The only Tour updates in those days were an occasional list of stage winners and, if we were very lucky, an updated top 10 GC, all hidden within the dreaded “Other Results” buried in the back pages of the Sports section of daily newspapers and usually secreted under all the football stuff that had already been reported elsewhere.

The cycling results were so small and so barely legible that they would have given actual small-print a bad name, and corporate lawyers a hard-on that could last for weeks.

Beyond these barest, most perfunctory of details, we restlessly devoured stage reports in Cycling (this was so long ago that it was even before the profound and dynamic name change to “Cycling Weekly”) to try and get a feel for the drama and the ebb and flow of the ongoing battle, but what came through was a generally disjointed and less than the sum of its parts.

For the young cycling neophyte the biggest treasures were a series of books published by the Kennedy Brothers following the narrative of each Grand Tour, imaginatively titled “Tour ’77” or “Giro ‘73” (you get the picture).

Although published weeks after the publicity caravans had packed away their tat and as the gladiatorial names garishly graffiti’d on the roads slowly began to fade, these books told a compelling narrative of the race, from the first to last pedal stroke, replete with some stunning high quality photos.

Opening the crackling white pages you could inhale deeply and almost catch a faint whiff of the sunflowers, Orangina and embrocation, as you were instantly transported to the side of the road to watch the peloton whirring by.

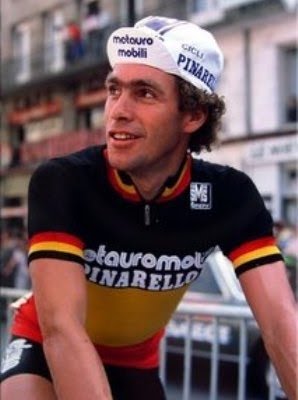

It’s in one of these Tour books that I first stumbled across a full-page photo of a boyish, fresh-faced young man, posed with some faceless fat functionary to receive a completely bizarre gazelle-head plaque. This may have been a prize for winning a stage, or the mountains classification, having the most doe –like eyes in the peloton, successfully passing through puberty, or something like that.

What struck me most though was that this hardened, elite, professional athlete didn’t look all that different from me – he wasn’t all that tall, very slight of build and looked so young – creating the impression of an instant underdog.

I would also later learned that under the jauntily perched cap was a head that would be subjected to some criminally bad hair moments too – instant empathy, although I never sank quite as low as having a perm.

It was hard to believe this rider was capable of comfortably mixing it up with the big, surly men of the peloton, with their hulking frames, chiselled legs, granite faces and full effusions of facial hair. Not only that, but when the road bent upwards he would fly and leave everyone grovelling helplessly in his wake.

The young man is Lucien Van Impe and the accompanying chapter of the book is titled Van Impudence, and relates in detail how he defied the hulking brutes of the peloton and their supreme leader King Ted, to wreak his own brand of cycling havoc in the mountains.

It was here that began my long-standing love affair with the grimpeurs, the pure climbers of the cycling world, those who want to defy gravity and try to prove Newton was a dunce.

Watch any YouTube videos of the time and you’ll see the big men of the Tour grinding horribly uphill, their whole bodies contorted as they attempt to turn over massive gears and physically wrestle the slopes into submission.

Merckx, indisputably the greatest cyclist of all time is probably the worst offender, and looks like he’s trying to re-align his top tube by brute strength alone, while simultaneously starring in a slow-motion film of someone enduring a course of severe electro-shock therapy.

Then look at Van Impe, at the cadence he’s riding at, the effortless style and how he flows up the gradients. Woah.

His one-time Directeur Sportif, and by no means his greatest fan, Cyrille Guimard would say, “You had to see him on a bike when the road started to rise. It was marvellous to see, he was royally efficient. He had everything: the physique, fluidity, an easy and powerful pedalling style.”

In his book, Alpe d’Huez: The Story of Pro Cycling’s Greatest Climb, Peter Cossins writes that, “Van Impe’s style is effortless and majestic. Watching him, one can’t help but think that riding up mountains is the easiest thing in the world. His is no heavy-footed stomp, but an Astaire-like glide.”

Many cycling fans prefer the rouleurs and barradeurs, the big framed, hard-men, the grinders who churn massive gears with their endless, merciless attacks, dare-devil descending and never-say-die attitudes.

Others seem to like the controllers who grind their way to victory, eating up and spitting out mile after mile of road at a relentless, contained pace, regardless of whether they’re riding a time-trial, a mountain stage or across a pan flat parcours.

For me though pure poetry lies in those slight, mercurial riders, who would suddenly be transformed – given wings and the ability to dance away from the opposition when the road tilts unremittingly skyward.

Even more appealing, they’re all just a little skewed and a bit flaky, wired a little bit differently to everyone else or, as one of my friends would say, “as daft as a ship’s cat”. The best can even be a little bit useless and almost a liability when the roads are flat, or heaven forbid dip down through long, technical descents.

The power of the Internet and YouTube in particular has even let me rediscover some of the great climbers from before my time, the idols who inspired Van Impe, such as Charly Gaul and Federico Bahamontes.

This pair, the “Angel of the Mountains” and “Eagle of Toldeo” respectively, both had that little bit of extra “climber flakiness” to set them apart. Bahamontes was terrified of descending on his own and was known to sit and eat ice-cream at the top of mountains while waiting for other riders so he had company on the way down.

Gaul’s demons were a little darker, once threatening to knife Bobet for a perceived slight and for a long period in his later life he became a recluse, living in a shack in the woods and wearing the same clothes day after day.

As Jacques Goddet, the Tour de France director observed, Van Impe also had “a touch of devilry that contained a strong dose of tactical intelligence” and was referred to as “l’ouistiti des cimes” – the oddball of the summits in certain sections of the French press.

Goddet went on to describe the climber as possessing “angelic features, always smiling, always amiable,” and yet Van Impe was known to be notoriously stubborn and difficult to manage, requiring careful handling, constant reassurance and a close coterie of attendants who would cater to his every whim away from the bike.

Cyrille Guimard, who coached, cajoled, goaded and drove Van Impe to his greatest achievement, Tour de France victory in 1976, described him as “every directeur sportif’s nightmare.”

While I’ve enjoyed watching and following many good and some great riders, it’s always the climbers who’ve captivated me the most, although just being a good climber doesn’t seem to be enough. In fact it’s quite difficult to define the exact qualities that I appreciate – Marco Pantani and Claudio Chiapucci never “had it” and nor does current fan favourite and, ahem, “world’s best climber” the stone-faced Nairo Quintana.

There has to be a little something else, some quirk or spark of humanity that I can identify with and that sets the rider apart and makes them a joy to watch and follow. Of today’s climbers I’m most hopeful for Romain Bardet – he seems to have character, style and a rare intelligence, but only time will tell if he blossoms into a truly great grimpeur.

From the past, our very own Robert Millar of course was up there with the best (although my esteem may be coloured by intense nationalism). Andy Hampsten, on a good day, was another I liked to watch and, for a time the young Contador, when he seemed fresh and different and believable.

Still, none have come close to supplanting Van Impe in my estimation and esteem. He would go on to win the Tour in 1976 and perhaps “coulda/shoulda” won the following year, if not for being knocked off his bike by a car while attacking alone on L’Alpe D’Huez. See, that sort of shit happened even back in the “good, old days.”

By the time Van Impe’s career was finally over (including a retirement and comeback) he’d claimed the Tour de France King of the Mountains jersey on a record 6 separate occasions (matching his hero Bahamontes) and a feat that has never been bettered. (Fuck you Richard Virenque and your performance enhanced KoM sniping, I refuse to acknowledge your drug enabled “achievements”).

In contrast, both during and after his professional career, Van Impe never tested positive, never refused a doping test and has never been implicated in any form of doping controversy – he’s either incredibly, astonishingly lucky, clever and cunning, or the closest thing you’ll ever get to the definition of a clean rider.

So, if you follow the Kitty Kelley premise that “a hero is someone we can admire without apology,” then Van Impe resolutely ticks all the boxes for me.

During his career he also managed to pick up awards for the most likeable person in the peloton and the Internet is replete with video and images of him as a good-natured and willing participant in some weirdly bizarre stunts, such as his spoof hour record attempt – proof he was an all-round good guy who never seemed to take himself too seriously.

In all Van Impe completed an incredible 15 Tour’s, never abandoning and was an active participant and presence in all of them.

He won the race in 1976 and was 2nd once and 3rd on three separate occasions, finishing in the Top 5 eight times. Along the way he won 9 individual stages and achieved all this while riding for a succession of chronically weak teams and competing when two dominant giants of the sport, Merckx and Hinault, were in their pomp.

Van Impe was also 2nd overall in the Giro, winning one stage and two mountains classifications on a couple of rare forays into Italy.

Not just a one-trick pony though, he could ride a decent time-trial and won a 40km ITT in the 1975 Tour, when he handily beat the likes of Merckx, Thévenet, Poulidor and Zoetemelk.

Even more surprisingly for a pure climber he even somehow managed to win the Belgian National Road Race Championship in 1983 after coming out of retirement.

I’m not sure if this represents Van Impe’s skills and talent, a particularly favourable parcours, or simply the nadir of Belgian cycling. Maybe all three?

In October this year Van Impe turned 70 and until recently was still actively engaged in cycling through the Wanty-Groupe Gobert Pro-Continental Team. He lives with his wife, Rita in a house named Alpe D’Huez, a reminder of the mountain where he set the foundations for his greatest triumph and perhaps suffered his most heartbreaking defeat.

Not bad for the one time newspaper delivery boy and apprentice coffin-maker from the flatlands of Belgium.

Vive Van Impe!